400 years of research in sunspots

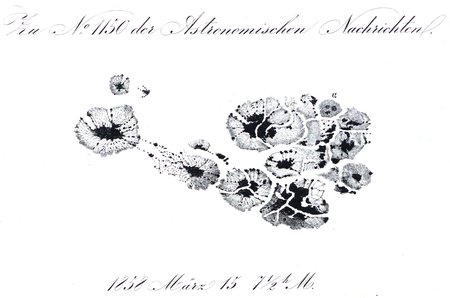

Very detailed pencil drawing of a group of sunspots by Samuel Heinrich Schwabe in 1858, published in Astronomical Notes.

Credit: AIP archiveThe first scientific article about sunspots was published 400 years ago on 23 June 1611. Scientists of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) and the University Oulu in Finland are now reconstructing tens of thousands of sunspots: the solar activity over four centuries. Looking back on history, they also want to understand better the future of the activity of the Sun.

The history of research on the activity of the sun goes back 400 years when Johannes Fabricius published the first article on sunspots on 23 June 1611. Numerous observers have recorded sunspots ever since. One of the many historical sources is just being harvested. The Royal Astronomical Society treasures the extensive collection of astronomical observations by Samuel Heinrich Schwabe made in the 19th century from Dessau, Germany. Tens of thousands of new sunspot positions are currently being measured and analysed by the scientists in Germany and Finland from the historical drawings of the sun.

Sunspots are an easy-to-detect indication of the magnetic activity of the sun. They came almost immediately into the view of the first telescopes that were directed to celestial bodies in the early 17th century. Johannes Fabricius was the first to have a detailed pamphlet printed which he dedicated to Enno III, the count of East Frisia, on 23 June 1611. Many observers of sunspots followed. One of them is Samuel Heinrich Schwabe who was located in the town of Dessau in Saxony-Anhalt and who left us with more than 12,000 solar observations. The excellent drawings of the sun are now being analysed by researchers from the AIP and the University of Oulu. Today we know that the solar activity varies with an average period of 11 years, and Schwabe was the first who published this periodicity in the sunspot numbers. The exact properties of four early cycles will be determined with Schwabe’s drawings of the solar disk.

Although the observations by Schwabe are not as old as the ones by Fabricius, they very nicely extend to the long time-series made at Greenwich Observatory of more than a hundred years into the past. “The solar observations by Schwabe are very precise and are accompanied by numerous verbal descriptions of the surface appearance of the sun,” explains Dr. Rainer Arlt from the AIP who is leading the project. “The space physicists of the University Oulu are working to study early solar activity by several methods, and this historical material is a real treasure”, comments Prof. Kalevi Mursula from Oulu.

Mechanisms for generating magnetic fields in stars and the sun are fairly well known, but it is still not possible to mimic the solar activity in a simulation solely based on basic physical principles. It is even more demanding to predict the activity in the future. Once we have a full record of sunspot positions and sizes over the entire period of telescopic observations of the sun, we will have much better constraints a successful theory should reproduce.

Further information

Daily high-resolution images of the Sun provided by the Solar Dynamics Observatory: www.spaceweather.com

Images

Very detailed pencil drawing of a group of sunspots by Samuel Heinrich Schwabe in 1858, published in Astronomical Notes.

Big screen size [1000 x 663, 70 KB]

Original size [1927 x 1278, 190 KB]