Milky Way shaken... and stirred

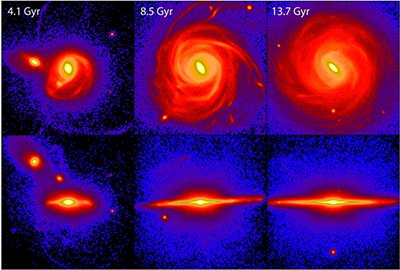

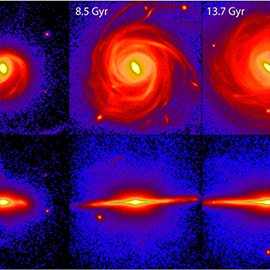

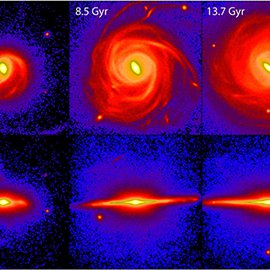

Three stages of the evolution of the galaxy simulation used to model the Milky Way. Face-on (top) and edge-on (bottom) stellar density contours are shown for each time. Each square panel has a side of about 117,500 light years. The mass and frequency of satellites galaxies interacting with the disc decrease with time.

Credit: AIPA team of scientists headed by Ivan Minchev from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) has found a way to reconstruct the evolutionary history of our galaxy, the Milky Way, to a new level of detail. The investigation of a data set of stars near the sun was decisive for the now published results.

The astronomers studied how the vertical motions of stars - in the direction perpendicular to the galactic disc - depend on their ages. Because a direct determination of the age of stars is difficult, the astronomers instead analyzed the chemical composition of stars: an increase in the ratio of magnesium to iron ([Mg/Fe]) points to a great age. For this study, Ivan Minchev’s team took advantage of high-quality data regarding stars close to the Sun from the RAdial Velocity Experiment (RAVE). The scientists found that the rule of thumb “the older a star is, the faster it moves up and down through the disc” did not apply to the stars with the highest magnesium-to-iron ratios. Contrary to expectations, scientists observed an extreme drop in the vertical speed for these stars.

To understand these surprising observations, the scientists ran a computer model of the Milky Way, which allowed them to examine the origin of these slow-moving, old stars. After studying the computer model, they found that small galactic collisions might be responsible. It is thought that the Milky Way has undergone hundreds of such collisions with smaller galaxies in the course of its history. These collisions are not very effective at shaking up the massive regions near the galactic center. However they can trigger the formation of spiral arms and as a consequence move stars from the center of the Galaxy to the outer parts, where the Sun is. This “radial migration” process is able to transport outward old stars (with high values of magnesium-to-iron ratio) and with low up-and-down velocities. Therefore, the best explanation for why the oldest stars near our Sun have such small vertical velocities is that they were forced out of the galactic center by galactic collisions. The difference in speed between those stars and the ones born close to the Sun thereby betray how massive and how numerous the merging satellite galaxies were.

AIP scientist Ivan Minchev: “Our results will enable us to trace the history of our home Galaxy more accurately than ever before. By looking at the chemical composition of stars around us, and how fast they move, we can deduce the properties of satellite galaxies interacting with the Milky Way throughout its lifetime. This can lead to an improved understanding of how the Milky Way may have evolved into the Galaxy we see today.”

The article “A new stellar chemo-kinematic relation reveals the merger history of the Milky Way disc” was published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters on January 20.

Science contact: Dr. Ivan Minchev, +49 331-7499 454, iminchev@aip.de

Media contact: Kerstin Mork, +49 331-7499 469, presse@aip.de

Three stages of the evolution of the galaxy simulation used to model the Milky Way. Face-on (top) and edge-on (bottom) stellar density contours are shown for each time. Each square panel has a side of about 117,500 light years. The mass and frequency of satellites galaxies interacting with the disc decrease with time.

Credit: AIPA team of scientists headed by Ivan Minchev from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) has found a way to reconstruct the evolutionary history of our galaxy, the Milky Way, to a new level of detail. The investigation of a data set of stars near the sun was decisive for the now published results.

The astronomers studied how the vertical motions of stars - in the direction perpendicular to the galactic disc - depend on their ages. Because a direct determination of the age of stars is difficult, the astronomers instead analyzed the chemical composition of stars: an increase in the ratio of magnesium to iron ([Mg/Fe]) points to a great age. For this study, Ivan Minchev’s team took advantage of high-quality data regarding stars close to the Sun from the RAdial Velocity Experiment (RAVE). The scientists found that the rule of thumb “the older a star is, the faster it moves up and down through the disc” did not apply to the stars with the highest magnesium-to-iron ratios. Contrary to expectations, scientists observed an extreme drop in the vertical speed for these stars.

To understand these surprising observations, the scientists ran a computer model of the Milky Way, which allowed them to examine the origin of these slow-moving, old stars. After studying the computer model, they found that small galactic collisions might be responsible. It is thought that the Milky Way has undergone hundreds of such collisions with smaller galaxies in the course of its history. These collisions are not very effective at shaking up the massive regions near the galactic center. However they can trigger the formation of spiral arms and as a consequence move stars from the center of the Galaxy to the outer parts, where the Sun is. This “radial migration” process is able to transport outward old stars (with high values of magnesium-to-iron ratio) and with low up-and-down velocities. Therefore, the best explanation for why the oldest stars near our Sun have such small vertical velocities is that they were forced out of the galactic center by galactic collisions. The difference in speed between those stars and the ones born close to the Sun thereby betray how massive and how numerous the merging satellite galaxies were.

AIP scientist Ivan Minchev: “Our results will enable us to trace the history of our home Galaxy more accurately than ever before. By looking at the chemical composition of stars around us, and how fast they move, we can deduce the properties of satellite galaxies interacting with the Milky Way throughout its lifetime. This can lead to an improved understanding of how the Milky Way may have evolved into the Galaxy we see today.”

The article “A new stellar chemo-kinematic relation reveals the merger history of the Milky Way disc” was published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters on January 20.

Science contact: Dr. Ivan Minchev, +49 331-7499 454, iminchev@aip.de

Media contact: Kerstin Mork, +49 331-7499 469, presse@aip.de

Images

Three stages of the evolution of the galaxy simulation used to model the Milky Way. Face-on (top) and edge-on (bottom) stellar density contours are shown for each time. Each square panel has a side of about 117,500 light years. The mass and frequency of satellites galaxies interacting with the disc decrease with time.